The Free Jazz movement of the mid-to-late 20th century is one of America’s most profound yet underappreciated bodies of music. Beginning in proper with the works of Ornette Coleman in the early 60s, Free Jazz became a paramount stream of art and Black experimentalism at the intersection of Black music, revolutionary literature, and philosophy. In the days of the Black Lives Matter movement and recent rallying around Black creatives as part of a response to systemic racism, KVRX has a special platform and responsibility to promote new and exciting Black creatives as well as preserve the cultural memory of those that came before them. Additionally, as people begin to further educate themselves with the works of Black liberationist thinkers such as Angela Davis and Frantz Fanon, taking a look at a musical movement steeped in some of those ideas can be a fruitful experience.

John Coltrane, Photograph by JP Jazz Archive/Redferns via Getty

Free Jazz gets its name from a near 40-minute improvisation headed by Texas-born and New York-famous Ornette Coleman. Coleman’s avant-garde stylings—which were met with harsh criticism and scorn by numerous critics—helped to shift the style of many key jazz players of the time into deeper explorative and expressive ranges. Some may point to earlier recordings by bandleaders, such as Lennie Tristano’s 1949 “Intuition,” as being early examples of free improvisational playing, but Free Jazz as a social and political form of Black avant-garde music first formed around Ornette’s influence.

“We’re going to create something they can’t steal because they can’t play it.” Free Jazz takes this to an extreme by escaping pre-existing Western conceptions of music in a musical embodiment of “Black is Beautiful.”

One of the constant criticisms of Free Jazz is that it has an overly “aggressive” sound. Although the genre can often be cacophonic, this criticism shows a slight misunderstanding of what the music aims to do in the first place. Given the state of jazz up to that point—from white artists like the “Original Dixieland Jazz Band” unabashedly stealing Black jazz forms in the 1910s, to the 50s white co-opting of bop with “cool jazz”—I’m reminded of this Thelonious Monk quote in which he references the incredibly unique formal styles of him and other bop boundary-pushers: “We’re going to create something they can’t steal because they can’t play it.” Free Jazz takes this to an extreme by escaping pre-existing Western conceptions of music in a musical embodiment of “Black is Beautiful.” This new slogan of the 1960s was expounded by thinkers like Walter Rodney, who argued for the deconstruction of both economic and cultural oppression in the West Indies.

Audio of Albert Ayler playing at John Coltrane’s funeral per Coltrane’s request. Note Ayler removing the saxophone from his mouth to scream towards the end.

One of the aims of Black liberation thought was a subversion of Western cultural superimpositions. This caused a shift in ideas of spiritual and religious freedom as Black leaders like Malcom X adopted other religions such as Islam. Amiri Baraka, a writer and follower of the Free Jazz movement who later founded the Black Arts Movement, often identified himself with the Arabic prefix “Imamu,” meaning “spiritual leader,” on his musical releases. This transcendence of Western religious structures was also reflected within music itself through the crafting of the emphatically Black musical form called “Spiritual Jazz.” Artists like John and Alice Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, and Don Cherry drew ideas from both African and Asian religious traditions to create the genre out of free styles. Ayler, more specifically, falls into Spiritual Jazz for his riffing on ideas from actual traditional spirituals, thus creating a unique blend of past and future sounds. Ayler's “The Truth is Marching In,” for example, is a reference to “When the Saints Go Marching In.” The spirituality of the Free Jazz “Holy Trinity” (Coltrane, Ayler, and Sanders) was praised by Joe McPhee as drawing him to the saxophone—the instrument on which he earned prominence with his now-classic 1971 free-funk “Nation Time” record, borrowing the name from Baraka’s “African Visionary Music” LP. To this day, McPhee still actively explores today in new free-improvisational releases. The ESP label was an invaluable space for this new school of playing to articulate itself in now-obscure players like Frank Wright and Giuseppi Logan.

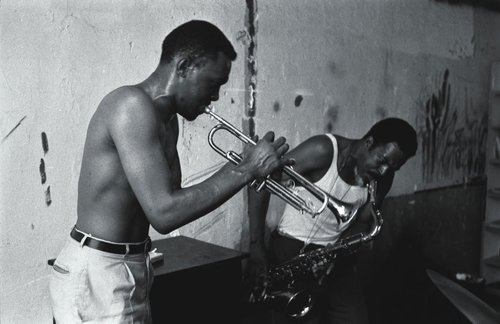

Donald and Albert Ayler, Photo by Val Wilmer(?)

Still present in much Free Jazz is the message of Black liberation and self-determination. One major example is the way in which the music resists economic imperialism and commercial exploitation by creating a challenging listening experience. While these artists certainly had more trouble playing in normal jazz clubs and signing to record companies, their work was never co-opted into a half-baked form more suitable for mass white audiences like almost all jazz before (Philippe Carles and Jean-Louis Camoli delve into this more Marxist way of interpreting Free Jazz in their book “Free Jazz/Black Power”). Some critics, like Baraka, also note the similarity between “overblowing” into the instruments to a sort of charged “scream” against injustice, oppression, and the murder of Black people. This is one grounded interpretation, but another aspect of the music's time that's worth noting is the political act of creating a purely Black avant-garde that questions the white "western" listener’s viewpoint of what music and artistic “beauty” truly are and can be. Malcolm X and Kwame Ture are quoted in Carles and Camoli's book discussing new jazz experiments, with X saying it reflected a completely new power to create previously unseen philosophies and systems. These Black artists asserted a new vision of musical form and ideation. Sunny Murray, for example, is said to be the “first drummer to play the theory of relativity” in his revolutionarily expressive manner of drumming, turning the idea of drums as simply a time-keeping instrument on its head. Much of this is also tied to the use of African instruments and complex African polyrhythms as an anticolonial reclamation, and a recognition of Black history. This is evident in Archie Shepp and Murray’s performance with a group of Algerian musicians playing traditional drums at the 1971 Pan-African Festival. The emphasis on African sounds and culture further shifted to include Third World concerns as Black liberationists spoke up about Third World liberation efforts and concerns.

This poetic connection held by Free Jazz is by no means an isolated case, and its depths help to prove the artistic and cultural significance of Free Jazz as a liberating force in Black experimentalism.

Interestingly, this connection to Third World liberation can be seen in Shepp’s Pan-African Festival album as it credits Ted Joans with a poem read of “We Have Come Back” at its beginning. Joans’ poetic output in the late 60s in books like Black Pow-wow often explicitly argues for Black liberation, but also for liberation in countries affected by economic imperialism and exploitation. His poetry is even more nuanced through his incorporation of the time's developments in jazz music into its rhythmical mechanics. This poetic connection held by Free Jazz is by no means an isolated case, and its depths help to prove the artistic and cultural significance of Free Jazz as a liberating force in Black experimentalism. Archie Shepp himself incorporates political poems to Malcolm X on “Fire Music” and “Poem for Malcolm.” Shepp personally reads his poem “Scag” between explorative free jams on “New Thing at Newport,” an LP he splits with a personal favorite Coltrane jam of mine. Jazz poetry itself has existed since jazz itself has existed. Langston Hughes’ jazz-accompanied readings, for example, are invaluable cultural documents in and of themselves.

Cecil Taylor, Photograph © Kathy Sloane

The tradition of jazz poetry was continued by Baraka in the 60s as he released "Nation Time," read with Sun Ra’s Arkestra (while still going by LeRoi Jones, on “A Black Mass”) and even Albert Ayler and Sunny Murray (on “Sonny’s Time Now”), bringing jazz poetry in conversation with a new dimension of sound and music. Meta DuEwa Jones in “The Muse is Music” points out how Sonia Sanchez, in “a/coltrane/poem,” deliberately borrows from Coltrane’s innovative musical mindset in augmenting her voice, showing the influence of these experimental jazz-based ideas on the Black Arts Movement. This rethinking of “voice” in the context of Free Jazz is also present in the vocals of Linda Sharrock (wife of Free Jazz guitarist Sonny Sharrock) and Leon Thomas (vocalist on many Pharoah Sanders releases). It’s notable that, although it was not a feminist movement by any visible means, Free Jazz influenced numerous Black female artists. Archie Shepp and Sun Ra are mentioned by name in the Ntozake Shange’s classic Black feminist choreo-poem “for colored girls who have considered suicide,” another important experiment in text and voice. On the 1970 LP, "SNCC's Rap," Leon Thomas notably makes the “free” use of his throat in the political protest on “Ain’t Goin’ to Viet Nam,” among other tracks including speeches by Black Power advocate H. Rap Brown.

Roscoe Mitchell and Moor Mother, Photo: Martin Morissette

In today's age, Free Jazz continues to inspire numerous Black artists and creatives of all generations. Prominent young poet and musician Moor Mother called the music a “liberation technology” that helped her expand her artistic vision. In particular, Moor was inspired by the Art Ensemble of Chicago and worked with them to incorporate her poetry into their music in the tradition of Free Jazz history. The afro-futurism of Free Jazz collective, Irreversible Entanglements, draws upon movement-titan Sun Ra’s own invention of it itself in his early interstellar music, continuing to inform many diverse works of Black creatives. Matana Roberts in her 2019 album continues her powerful Coin Coin series and lays down many pieces in the free-music realm. The Chicago Underground Quartet recently released its free-jazz-informed album as well. All of these artists draw upon this Black experimental history to help craft a new vision. In the words of Cecil Taylor, they use the music in the ancient, liberating tradition of achieving a “levitation or trance which is the existence beyond the normal existence” while continuing to assert their Black voices.

Matana Roberts, Photo: Roger Thomas