The Dalai Lama’s new album Inner World, released on his 85th birthday, drew attention as something of an oddity. The leader of Gelug Buddhism, and a paramount figurehead of Tibet, had never dropped an album before, which makes it an interesting point in both his history and the history of recorded Buddhist music. Many western people’s encounters with Buddhist music have been in the form of various New Age “music for meditation” or “relaxation” releases. In themselves, these can serve as decent auditory introductions, but often lack rooted tradition or are commercial re-packagings of the traditional liturgy (look no further than releases like “25 Buddhist Vibes” on Spotify).

At first glance, “Buddhist music” might seem to be something of a contradiction. Indeed, many Buddhist traditions do have precepts against seeking worldly music, preaching a shedding of attachment to outward musical forms. For this reason, much Buddhist music points to the inner Buddha-nature and often has more to do with direct participation of the music than listening to it. Suizen, for example, was practiced by a small Fuke sect of Zen Buddhism in Japan and sought enlightenment through bamboo flute playing. This type of music consisted of blowing sometimes just single notes for long periods of time, alongside traditional compositions intended for private reflection rather than public performance. Far from the pinnacle of Buddhist music, it nonetheless gets at the personal nature of the practice, focusing on the “inner world” and the ability for enlightenment that is shared by all beings.

The Dalai Lama at 85; Credit: Ven Tenzin Jamphel

Most Buddhist music or aural liturgy stems from oral recitation of sutras and prayers due to the lack of a written tradition in the time of Buddhism’s origin. Sutras are distinct from prayers in that they are teachings of the Buddha or scriptures that carry authority as words of Buddhas. This oral recitation has led to chants and mantras being almost universal across Buddhist tradition, and therefore most ethnomusicological recordings of Buddhist music are of various chants.

The lyrics on Inner World are mostly made up of repeated mantras, largely in Sanskrit (the language of many classical Indian sacred texts including most Mahayana Buddhist sutras). Given that the Tibetan Vajrayana—or Tantric—realm of Buddhism was born out of the later Indian Mahayana Buddhism, there is an overlap of certain texts and sutras that are common to Tibet and across eastern Asia. This manifests itself on this release with the Lama’s chanting of key Sanskrit Buddhist mantras alongside Tibetan ones. Bangali sitar player Anoushka Shankar’s appearance on “Ama La” seems to symbolize the influence of Indian music and mantra on Tibetan Buddhism. In his commentary on the Heart Sutra, Buddhist student and translator Red Pine describes mantras as “knowledge that transcends our normal understanding of knowledge” and as the “creation of beings in touch with the underlying vibrations of the mind” often not meant to be understood by normal concepts of language. Another way to contextualize mantras is through the Tibetan tradition of deity visualization in meditation. Mantras in this way are often used to end the dichotomy between the practitioner and the deity, like the “om muni muni” chant on “The Buddha.”

Tibet is home to almost countless musical traditions, varying at each monastery within the already distinct Four Traditions (including the Dalai Lama’s Gelug tradition). One of the most well-known is the throat-singing or overtone-singing technique used by several monasteries. These vocals are created using throat techniques that cause drones of multiple notes at once. This technique is somewhat well-known in its Mongolian or Tuvan forms, but too often treated as a strange, exotic novelty. Originating in Mongolia, throat-singing was a deeply ecological cultural heritage born out of participating in the natural sounds surrounding Mongolian nomadic peoples. In Tibet, it exists as a non-rhythmic exercise that focuses entirely on the breath rather than the words of the chant. This self-dissolution into breath is something of a means for participants to shed their ego (the ego being the root of all suffering according to Buddhism); this is similar to other Tibetan practices like chöd, which can incorporate “improvised” vocalizing. While not all chants manifest in throat-singing, it and other practices can be seen in the light of Zen Master Dogen’s famous saying “the entire universe is the breath of the Buddha.”

Gyuto monks throat-singing; Credit: Minnesota Historical Society.

The variations in the rhythm (or lack of strict rhythm) are part of the tradition of vocal spontaneity found in Tibetan Buddhism. For instance, the Tibetan poet-saint Milarepa composed all of his famous verses and poems completely without forethought. This plays to the valuation of the “pure” mind and intuitive approach to reality found throughout Buddhism. This is the idea of prajna, a transcendental insight without the formulations of ego or absolute self. The chöd and throat-singing improvisations are drawn from this inner spontaneity, which also appears in the usually un-measured rhythm of the mantra chants on Inner World. This prajna wisdom is the exact idea embodied by Manjusri, the bodhisattva (being who vows to enlighten all other beings) to whom the mantra of “Wisdom” is dedicated to.

This shedding of the ego through artful recitation reminds me of the emphasis of recitation in Pure Land Buddhism (Amidism) and Nichiren Buddhism. Nichiren in particular left a mark on music, as jazz artists Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Buster Williams, and Bennie Maupin became Nichiren Buddhists, incorporating the famous mantra “Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō” from the Lotus Sutra into some of their improvisations. Maupin’s Jewel in the Lotus album is a reference to “Om mani padme hum” which appears on “Compassion” from Inner World. Through these artists as well, one can see the influence of mantra as a bridge from the Jazz Fusion movement to the New Age musical movement. An early antecedent to this crossover of Mahayana Buddhism and jazz was Tony Scott’s “Music for Zen Meditation” from 1964, which also incorporates sutra chants and mantras. Beat poet-improviser Allen Ginsberg notably drew inspiration from Milarepa and Buddhist thought in his poetry, the collection Mind Breaths being directly inspired by his Tibetan study. He was also significant in bringing mantras to the American masses in leading Indian Hare Krishna chants in the 60s, and even appearing on the Clash’s Combat Rock chanting the Heart Sutra mantra near the end of “Ghetto Defendant.”

Although the Dalai Lama’s album is not necessarily connected to the aforementioned jazz realm (I see the sax on “Wisdom” as an unintentional nod to this jazz), it can still be seen as part of both the wider New Age trend and the Tibetan Diasporic community utilizing new musical conventions. Kiela Diehl’s book “Echoes from Dharamsala” examines music in Tibetan refugee communities, following communities both reconstructing a near-lost heritage and younger Tibetans interacting with newer Western musical forms. It documents first-hand the tensions between the 90s Tibetan DIY rock group the Yak Band and monastic authorities, particularly over monks enjoying “worldly” entertainment that was nonetheless tied to the collective Tibetan identity.

Since the lyrics to the album (aside from tracks 1 and 3) are not available on Genius, here are the mantras I was able to transcribe, with accompanying information:

The second track, “The Buddha,” features the “Om muni muni maha muniye soha” which is a mantra in praise of Shakyamuni, another name of Gautama Buddha.

“Compassion” features the famous “Om mani padme hum” mantra, which is historically connected to Avalokitesvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. Avalokitesvara is one of the most prominent deities in all of Buddhism, and even delivers the core teaching of Mahayana Buddhism’s view of reality in The Heart Sutra. This mantra’s four words are usually taken to reflect Avalokitesvara’s four-armed form, and six syllables purifying the six senses. The Dalai Lamas of the Gelug school are believed to be incarnations of this bodhisattva. The idea of springing from a lotus contained in the mantra is even important to the origin of Vajrayana, contained in the name of Padmasambhava (“He who was born from a lotus”).

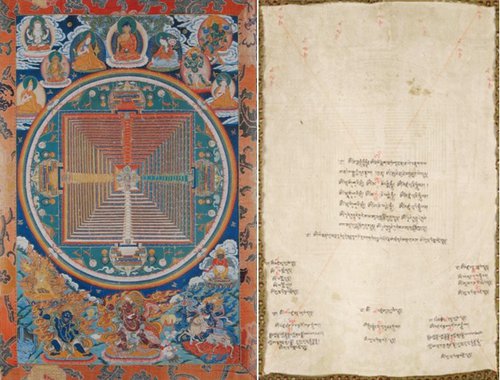

Mandala of Avalokitesvara, bodhisattva that is paid tribute to on “Compassion.” The Buddha is present at the very top of the painting, with wrathful protectionary buddhas similar to Hayagriva at the bottom. The circle of the mandala represents the path of life, with the 4 compass-directions being unified in the center. On the reverse, various mantras such as the Tara, Shakyamuni, and Avalokitesvara are inscribed. Credit: himalayanart.org, from “A Tale of Thangkas”

On “Wisdom” the mantra “Om ara baza na di” appears a dedication to Manjushri. Manjushri is the bodhisattva of wisdom in the Mahayana and Vajrayana canon, an embodiment of pure insight, or prajna.

“Courage” features a particularly interesting mantra to Tara in “om tare tuttare ture soha,” or the Green Tara mantra. Tara is a female Buddha in Tibetan Vajrayana who is seen to protect practitioners from fear and ignorance.

“Healing”’s mantra is that of the Medicine Buddha: “tayata, om bedkadze bedkadze maha bekadze bedkadze radza samungate soha.” According to Lama Zopa Rimpoche, “bekandze bekandze maha bekandze” contains the path of enlightenment and elimination of pain.

“Purification” has the most difficult mantra with “Namo ratna trayaya om kamkani kamkani rotsani rotsani trotani trotani trasani trasani pratihana pratihana sarva karma paramparanime sarva sattvanancha soha” (which I had to do some searching to find). Traditionally it is said to purify the negative karma often of the recently deceased, the mantra aimed at Akshobhya buddha.

In “Protection” appears the “hri benza krodha hayagriva hulu hulu hum pey” mantra to Hayagriva. Hayagriva is interesting in that they are the only “wrathful” deity paid tribute on this release. Tibetan Vajrayana differs from many other forms of Buddhism by incorporating wrathful buddhas that embody the strength of compassion and wisdom that is needed in practice.

Graphic By Alejandra Gavilanes